Today, more than six years after I first found old pika scat in the area, a study documenting extinction of the American pika from an unprecedentedly large region, has finally been published in the peer-reviewed journal PLOS ONE. Conservation science—with its meticulous data analysis, limited budget, and lengthy peer review process—can progress slowly. But what this study, and other studies, show is that large-scale range contraction from climate change can happen over a relatively short time span.

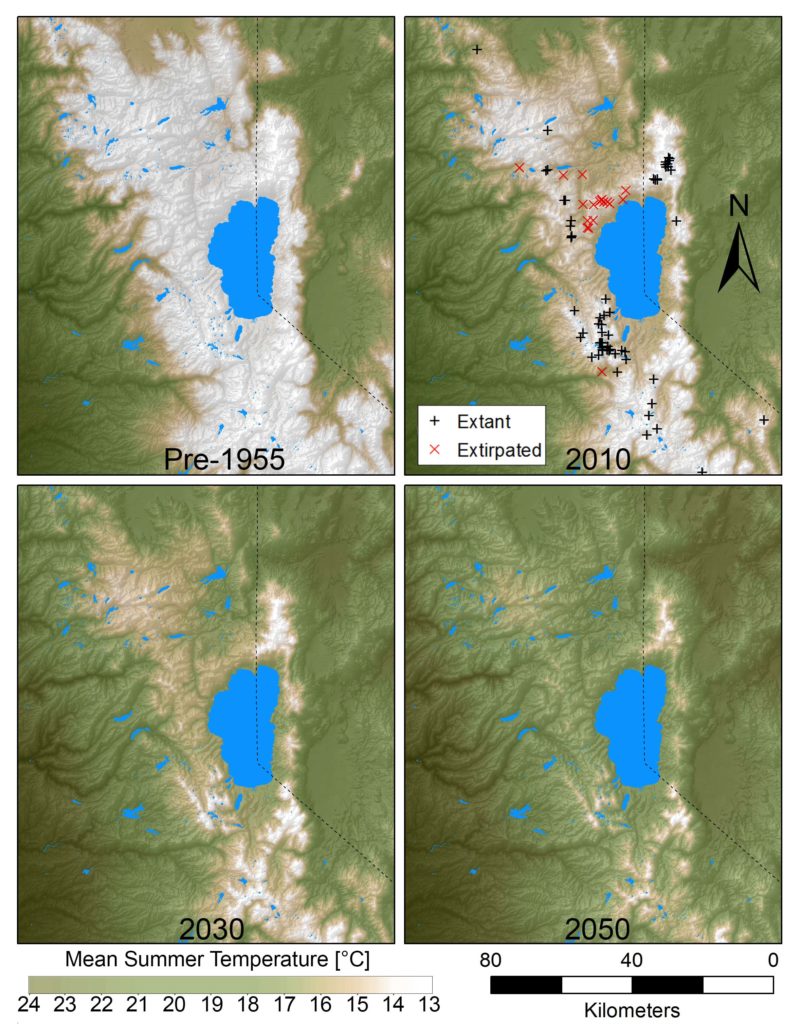

Map of the study area. We refer to the roughly triangular area surrounding Mt Pluto—bounded by Lake Tahoe, the Truckee River, and Highway 267—as the Pluto triangle. Radiocarbon dating was used to determine the age of old pika scat collected at extirpated sites within the triangle.

The study documents the extinction of pikas from a 165-km2 area of the northern Sierra—the largest area of pika extinction yet to be reported in the modern era. We refer to the area of extinction surrounding Mt Pluto as the Pluto triangle. The large spatial extent of the die-off echoes large-scale range collapses that happened when temperatures increased after the last ice age. Radiocarbon dating of relict pika scat recovered from the triangle indicates that pikas likely disappeared from many of the lower elevation sites surrounding Mt Pluto before 1955, but persisted near the peak as recently as 1991.

The local pika extinction opens a large gap in the pika’s distribution north of Lake Tahoe. Before their collapse, pika populations in the Pluto triangle region could be thought of as an isthmus of modest-elevation habitat connecting the mainland stronghold of pikas—the crest of the Sierra on the west side of Lake Tahoe—with a peninsula of pika habitat (Mount Rose/Carson Range) on the east side of Lake Tahoe. The triangle was central to a contiguous area of pika distribution. The loss of pikas from the triangle suggests the complete loss of metapopulation and genetic connectivity through this corridor.

The study also used local occupancy data to project future effects of climate change on pikas. By 2050, we predict the extent of climatically suitable land in the Lake Tahoe area will decline by 97%.

Decline in the area of climatically suitable habitat for pikas over time. The boundary between white and tan is the approximate threshold above which conditions become tenuous for pikas.

Worryingly, this isn’t the only large area where pikas appear to have recently gone the way of the dinosaurs. A study published last month in Western North American Naturalist documents both the discovery and apparent extinction of pikas from the Black Rock Range of Nevada. The extent of this extinction, depending on how you draw the boundaries, is at least ~45 km2. Another study, published last year in the Journal of Mammalogy, documents the apparent extinction of pikas from Zion National Park. Though the area of formerly occupied habitat in Zion appears to have been relatively small (< 3-km radius) it appears to constitutes the complete extinction of pikas from the national park. The apparent extinction of pikas from Zion National Park happened sometime between 2011 and 2015.

Of course it’s not just American pikas that are declining because of climate change. Nearly half of all plant and animal species that have been examined so far have already experienced local or regional extinctions that appear to have been caused by climate change. The first (documented) extinction of an entire mammal species due to climate change occurred sometime between 2011 and 2014. Our best estimate right now is that about one million species are vulnerable to extinction from climate change this century (one in six species on Earth). There are management actions we can take to help many of these species, but a far simpler (and more economical) solution than trying to save each of these species individually is to rein in and reverse climate change.

In the case of the American pika, and many other species vulnerable to climate change, more work is needed to establish baseline data so that future research can accurately measure the extent of their decline. The best strategy for conserving many of these species may involve targeted gene flow, wherein a small number of individuals will be translocated from warm-adapted populations to populations that lack these adaptations.